Adventure Report: NyenchingTanggula Sapu Mont Trek

Team member: Yu Liu, Shan Ren, Long Kui, "Two", “Little Demon”, Meng Qiang

Time: October, 2019

Length: 128km, 10 days

Location: Southeast Tibet

Difficulty: 7.5/10

DAY1 15.5km Atuoku Village-Sirongcuo Lake-Sirong Pass 5362m-Camp1

DAY2 10km Camp1-Maan Pass 5373m-Cabin

DAY3 8km Linlu Pass 5414m- Valley west of Sapu-Cabin

DAY4 14km Cabin-Yangqiong Pass 5485m-Samu Lake- Yangduo

DAY5 10.4km Samu Lake-Sana Pass 5490m-Glacier-Lvdumu Lake-Cabin

DAY6 13.6km Cabin-Monong River Valley-Dire-Naruo Village-Cabin

DAY7 20km Cabin-Sangqiong(Yingzui) Pass 5360m-Cabin

DAY8 15km Cabin-Jinlongqiu Mountain-Wujian Cuo Lake-Cabin

DAY9 15km Wujian Cuo Lake- unkown name Village

DAY10 8km Cabin-Chizu Vallage

I tried to record this adventure in a different style of writing.

PART I: DAY 7, LAST DAYS IN WILD

The rain kept falling, and as the elevation dropped, the ground became more and more muddy and watery, with mud puddles large and small stretching out in front of us into low-lying valleys further down the trail. The meadows slowly disappeared and the annoying bushes grew taller and progressively denser, blocking the view, a nerve-wracking situation.

‘Slow down, how long before we get to the camp?’

‘It’s still some distance, there’s an open field where the valley forks ahead, and going into the valley on the right, we’ll pass a couple of abandoned villages, and if we don’t get to that blue lake before sunset, we’ll have to camp in the villages.’

Stopping to rest was a luxury, and it was difficult to find a dry place to sit down. While stopping to wait for the rear party, I noticed the puddles on the road getting bigger and more defined in shape.

‘I’m afraid we’re going to have to go a little faster, the footprints here are clear and look like they’ve just been walked over.’

‘Is this a black or brown bear?’

‘It looks like a small brown bear. This way, we’ll take turns calling out and it will let the bear know we’re there.’

‘Hey! Ha! Hey!’

Crossing a swampy and slate-lined bridge, it looks like it was made by the locals, who set logs up side by side over the river, tied them up with rope, and laid pieces of stone they’d picked up from the river on top of them. If they didn’t, this raging mountain stream couldn’t even be crossed by a horse. On the other side of the bridge was an open field where stood several long-abandoned huts.

It was still raining, but the sun had made it impossible to keep your eyes open, the grass near by refracting a soft green light, the snow-capped mountains in the distance reflecting a strong white light. The clouds were quickly dispersed by the heat of the light, and I unconsciously turned backwards to avoid the glare, but found a rainbow standing over the river I had just walked across. In this place we were surrounded by strange light.

‘There’s a bear, look, is that a bear over there? Hurry!’

‘Right! Quickly get my camera.’

It had run away by the time I fetched my camera, stopping to look backwards at our uninvited guests as it ran, a hint of fear and curiosity in its movements at the same time.

During this season, brown bears in Tibet descend from the mountains around human villages due to food shortages, and the one just now was looking for food inside an abandoned house.

‘Hey! Ha! Hey!’

I saw a smashed wooden house, as if it had been struck by some huge object, with only one pillar standing there, on which hung a yak skull inscribed with scriptures, as if it were a totem. Several hundred metres of the mountainside behind the house had been cut down to nothing but stumps and hung with sutras.

Such steep bare slopes can’t hang snow in winter, and it is likely that an avalanche destroyed the house. The gods would have been helpless when they cut down the pine trees that protected their houses and turned to mysterious forces for help, right?

‘The sun is going down, we still have time to get to the lake, I can already hear the sound of a waterfall in the distance, that must be the outlet of the lake over there.’

From the satellite map, WujianCuo Lake is a large blue lake under glacier. In reality, it is surrounded by snow-capped mountains on three sides, and the water is fresh and clean, with a slight blue glow under the refraction of the setting sun.

At the head of the lake, there is a small piece of flat land, hung with streamers, as if for the organisation of some kind of ceremony used. The Tibetans believe that the lake under the sacred mountain is a goddess, and they make scripture-like coloured cloths into streamers and hang them in front of natural wonders, believing that they can obtain the blessings of the gods.

Unlike other religions, these gods are essentially nature itself. Tibetan Buddhism’s worship of nature originated in the indigenous and primitive Bon religion, and later Buddhism absorbed the Bon religion’s belief in the great mountains and lakes, forming the characteristics of what is now known as Tibetan Buddhism.

‘I checked the house, and it has cow dung and firewood and a furnace, so I should be able to stay here for the night.’

‘Will any beasts come?’

‘Don’t worry, the animals won’t bother us, we’ll put wood against the door, and with the smoke inside the house, they’ll know there’s someone here. The herdsmen have already taught them for us.’

Each abandoned house had scattered firewood, which we collected one by one and bagged. Then the firewood was dragged near the fireplace, breaking them with our boots, and put into the fire, which crackled and flared, and the fire was strong enough to dispel the dampness in the cabin.

The house was dry, the door was well blocked, and we could sleep in peace, and if felt cold, add some wood to the fireplace.

PART II: WHY WE WENT WILD

For modern people, cities represent civilisation and rationality, comfort and progress. Thousands of kilometres away from the city, in the Nyenching Tanggula Mountains, most of the people living there still lead a primitive life of herding and gathering. Most of the women in the mountains have no access to education and spend their lives raising horses and herding cows in the mountains.

Their villages are connected only by a dirt track, and although there are mobile phones, there is no internet, and the only use of electricity is for lighting. Their way of life is guided by Buddha, including food, even if a salmon swims into the bowl, they will not hesitate to pour it out.

Many people have asked me why I am so keen on travelling to places that are dangerously desolate, and if I had answered in a pop style, I probably would have said, as many people do, in puzzling words: because it’s there. But now that I have the time, I’m willing to tell the truth in my mind.

The city I live in has a population of 7 million and the urban area is only a few dozen kilometres to the north, south and east-west. Beyond these dense high-rise buildings and complicated roads, there are small villages.

The people who live there have their own houses in the city, but every weekend they go back to their homes, open the gates of their courtyards made of bamboo strips, and post their best menus to the side of the road, welcome to their guest.

They usually drive luxury cars and stay in star hotels on business trips, but now they don’t care whether the floor is paved with marble or red bricks, they don’t care about the leaves and dust scattered on the tables, even bird droppings and caterpillars may fall at any time when they dine under the big trees.

For these people, being away from a clean and dry city is at the same time being away from the nuisance that civilisation brings. If they have to choose between quality of life and disturbance, they will still choose to stay away from disturbance at special time, which is a means of healing for city dwellers. Going to experience a more primitive life essentially tends to establish a connection with nature, to repair one’s damaged spirit.

And my love of exploring the mountains has no different from those who enjoy have weekend food in village, both have the same aspirations and original intentions. But I prefer to get in touch with pure nature.

Eating wood-fired chicken under a big walnut tree won’t satisfy my desire to explore, so I have to go in search of the more remote and pure wilderness.

Where to look for? Of course, it is Xinjiang and Tibet, a large area of the mountains, where the traffic is inconvenient, there is no hotel, no tourists, I can group a small adventure team, free to explore. I will carry a backpack and a tent, and will not be surrounded by unrelated people.

PART III: 9 DAYS AGO

In order to improve the quality of life, team member Meng Qiang booked a guesthouse in Nagchu, Tibet that provides diffused oxygen supply. However, in order to adapt to the low-oxygen environment, I forbade everyone to switch on the oxygen valve.

It was already the fourth day since we arrived at the plateau, and if we inhaled oxygen for the sake of momentary comfort, the efforts of the previous four days would be wasted.

Due to the long hours of walking in the plateau mountains, I was able to take a long run even at 5,000 metres in Nagchu. So a nice bath was even less of a problem for me.

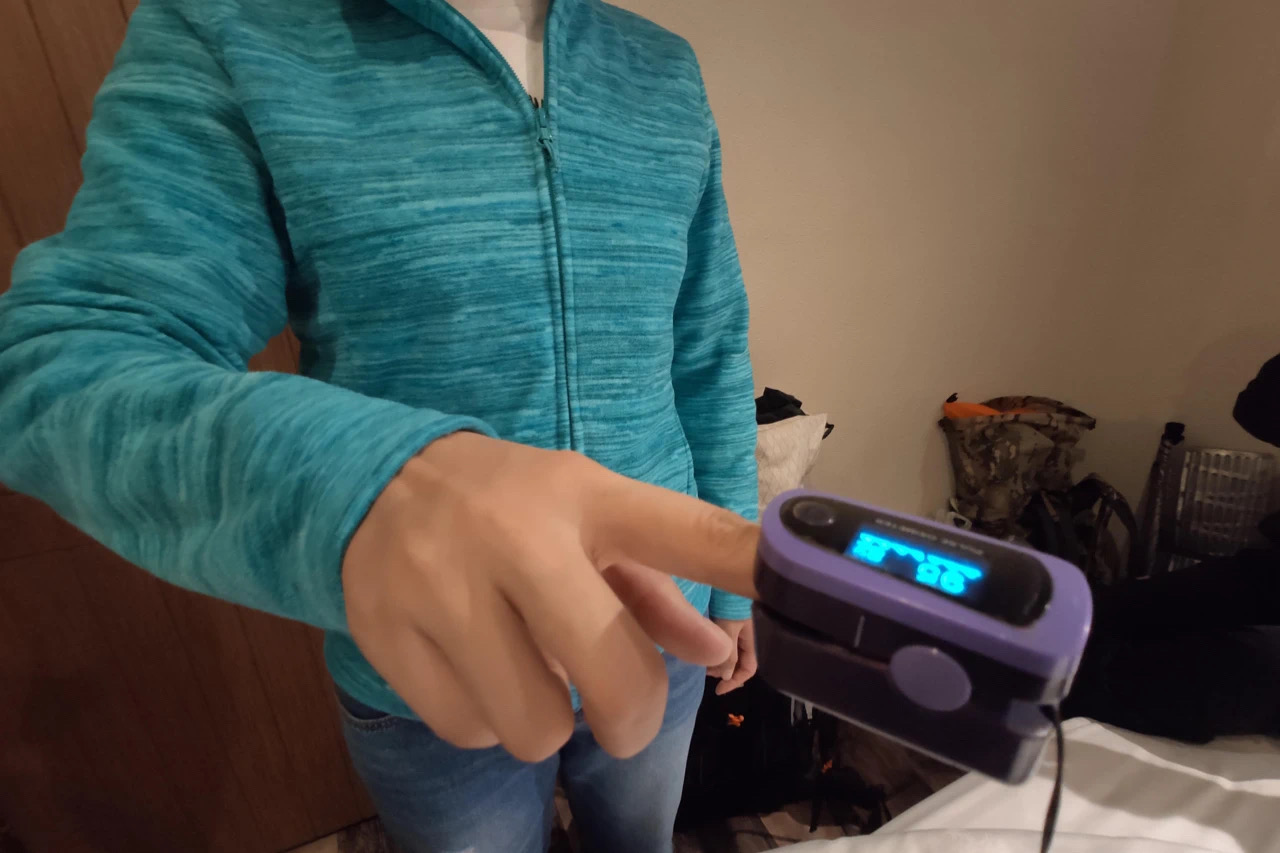

What I didn’t expect was that other team members also learnt from me to take a bath, and as a result, two female team members: Two and Demon showed symptoms of cold and fever that night, and their blood oxygen saturation dropped from over 90% to over 70%.

I turned the oxygen valve on as they needed it to increase their resistance to recover their bodies.

‘Yu, it’s been an hour and the blood oxygen hasn’t changed, what’s going on?’

‘It might not be oxygen, let’s try it. Light the tissue paper, close to the air valve, try to see if it burns more violently.’

I carefully put the burning paper close to the ‘oxygen’, but the flame didn’t change at all.

‘Shit, it’s fake oxygen.’

The town of Giali is the entry point to the mountains, and it is a 4-5 hour cross-country vehicle ride from Nagchu. Most Tibetan men need to have an ATV when they reach adulthood, otherwise they will not be able to move an inch on this vast and desolate roof of the world. One of the benefits of the ATV is that if they hit a barrier, they can go through the surrounding alpine meadows. I don’t know what they would need to bypass the barrier, presumably because they were carrying us outsiders?

By the time we reached the original entry point, it was already that night. There is a danger of encountering wild animals when camping by the roadside, but we chose to camp immediately as opposed to walking at night. The restaurant owner in the village told me that there had recently been a bear infestation, and that people had been killed by bears during the night, and that the villagers were terrified.

‘You must be careful, it’s best not to go into the mountains, there are too many bears.’ The village restaurant owner said.

‘It’s all right, there’s no food left in the mountains, the bears have all come down to look for food, it’s hard for us to meet bears.’

It would be a lie to say that there was no concern at all, after all, bears are also attracted to the smells from our tents. But I believe that being swatted by a bear is a small probability compared to a car accident.

PART IV: DAY2-DAY5 WESTERN FACE OF SAPUGANGRI

Photos of the northern face of Sapugangri are common on the internet, but the western face are rarely seen. If you look at the photos of the Western face at first glance, you’d think it was a mountain in Nepal or the Alps.

To see the Western face, you need to go over a rocky pass at an altitude of more than 5,300 metres, with no trail, which is unfamiliar to the locals.

In the middle of the pass there is a large stone paved platform, which is flat, but there are few plants willing to grow in such a barren place. In the middle of this platform is a blue ice lake set in the middle, which tells us that this was once a glacier.

‘We need to hurry, the weather is changing too fast.’

‘Okay, but the air is thin.’

The path to the pass is littered with scree, boulders that have flaked, crashed and cracked under glacial erosion and thermal expansion, full of sharp edges.

I wonder how the first Tibetans who came here found these paths. The so-called path is to walk through the rocks without a trace of dirt underfoot or any markings, like finding the optimal escape route in a maze.

The higher the altitude, the faster the weather changes, bad weather can strike at any time, and the lack of oxygen slows down the action and makes the danger even more dangerous. At this point, the only thing you can do is to save your strength and keep your mind clear.

When we reached a few dozen metres below the pass, a fierce snowstorm suddenly descended, visibility was instantly reduced, the back of the team disappeared into the wind and snow, the front team could only temporarily hide under a big rock for shelter.

‘Yu, it will be a long time before Shanren and Meng Qiang come up, should we wait? Or should we go over now?’

‘We must wait, or they won’t be able to find their way over the pass. Bring out the tents and mats, let’s hide under it.’

‘Yu, it will be a long time before Shanren and Meng Qiang come up, should we wait? Or should we go over now?’

‘We must wait, or they won’t be able to find their way over the pass. Bring out the tents and mats, let’s hide under it.’

Even though we just put the tent over our heads, it was much warmer inside than outside, and the wind and snow couldn’t blow in at all. A thin nylon sheet, a few people squeezed inside, heat and moisture filled the small space, on the outside was the vast stretching Nyenching Tanggula mountain range, but the cold wind and blizzard was raging.

By the time Meng Qiang and the others walked up, the snow had stopped, the sun was back out, the sky was clearer than before, and the deep blue colour made the snow seem unreal.

All the colours on us were more vibrant than before, and if I had tried to record the feeling with my camera, it would have had to be pulled up saturation.

The wind on the pass was nowhere to be found, and there was even some warmth standing in the setting sun, the snow hiding the footprints that had come, as strange as the sudden descent here.

The sun was setting and the shadows of the mountains were growing and lengthening along the ridgelines, and although we wanted to enjoy the afterglow of the setting sun for a little while longer, the shadows of the mountains were telling us that we needed to find the campsite asap.

Walking in such a barren land can be a more heartfelt way of thanking nature for the food and shelter it has given us. We’ve always thought of those things as mere products of industry and ingenuity, but here you realise that it’s more important what resources nature itself can provide.

If I hadn’t been hiding inside a tent made of petroleum and curled up in a sleeping bag made of bird down, I wouldn’t have been able to find anything that would have kept us alive on this windy, snowy night in this barren land.

The tent shook violently in the strong winds, and I could only pray that the fabric of the tent would resist the hypothermia and tearing, or I would lose my life. No wonder the locals worship the towering snow-capped mountains as if they were deities, faith becomes the only saving grace when through hard work one cannot provide support for survival.

In the morning when I drilled out of my ice-crusted sleeping bag, I found that the plastic water bag filled with water froze into an icy lump, and if it wasn’t for the strong plateau sunshine, I might have had to carry this big ice cube on my back to continue my trek.

From my review, the first four passes of this trek were all of the same type: above 5,300 metres in altitude, full of gravel or rocks, with no trail bed and steep gradients.

After the third pass, we reached the western slopes of Sapugangri, with a muddy road that goes right up to the glacier nearby, and two very modest, ventilated, air-sprinkled tin houses. Who wants to be huddled in a cramped tent when there is a house to live in, no matter what it is like.

I shoved cow shit into the roaring fireplace and the heat and smoke made the house dry and warm. The crew who had been out shooting the stars panicked and came back inside, telling that they had heard wolves howling, and we learnt to howl like wolves.

Maybe it was too much of a fake learning, and no more wolf howls outside.

PART V: DAY6-DAY8

Sapugangri north face of the glacial lake called ‘Samucuo Lake’, the lake has begun a modern infrastructure projects, keen sense of smell of commercial, this side of the row of view tin room, written: Visitor Assistance Centre xxx assistance in the construction of the. Here a bed 100 yuan(Around 15usd/ per person).

No separate room, no bathroom, no toilet. But after the hardships of the first few days, these conditions can already be very pleasant. At least one couple we met on the way was planning to stay here for a few more days.

But staying here is not without any worries, first of all, you will slowly begin to struggle with what to eat, is beef stewed potatoes or tomatoes scrambled eggs; internet will also make people more troublesome, if you send a post on instagram, it may be thought that this is a scenic spot, reducing the level of this adventure, if you do not send it, you will feel uncomfortable; the smell of the food here will attract a lot of uninvited guests. You have to worry about getting your head slapped off by a brown bear behind you when you shitting at night.

Talking of bears, we are not imagining things, in fact, there was a bear banging on the door in the middle of the night, and the Tibetan caretaker shouted at the door, and it soon left.

In terms of both mental torture and physical well-being, this was not a place to stay for long. We still decided to leave as soon as possible.

Walking to the foot of Mount Sapugangri, I realised that Samucuo Lake looks far less big on the map than it does in reality, and that at the location of the glacier marked on the map, it is now a green lake where the glacier has melted and retreated to the foot of the mountain.

Even at such a distance from civilisation, human industrial activity can affect every flower, plant, fish and insect, every rock and ice here. But can every change here affect people in the civilised and ‘rational’ world in the same way?

This is another reason why I love walking in the wilderness. I have an almost naïve hope that through the power of words, I can establish a weak link between people living in the civilised world and the wilderness.

Going east from Samucuo Lake over the glacier-covered snow-capped mountain passes, one reaches Naruo. There are villages there, as well as several snow-capped mountains and lakes, said to be the illegitimate sons and daughters of the god Sapu.

To get to Naruo, you have to go over a stretch of snow-covered mountains that are covered with glaciers and snow, with only a 5,490-metre gap to go over, which some people call the Sana Pass, but there is no way of verifying this name. Ask the locals and they simply reply, ‘There is indeed a trail over there.’

The Sana Pass is different from the previous ones in that it is covered by glaciers and snow, and to get over it safely requires a certain knowledge of glaciers, to know where to walk, and in the season of heavy snowfall, there may be a large number of dark crevasses distributed under the surface of the flat glacier. We couldn’t spot those crevasses, so we kept to marching on the lateral moraine.

The dark blue light was refracted from within the towering glacier, and beneath our feet were scorched gravel which, like thin mud, slid down half a step with each step. Under some of the scree were crevices in the ice, which had to be carefully probed with trekking poles or else you would fall.

On the glacier at the top of the mountain, a dark natural ice cave was found, nearly ten metres high, with three layers and smooth, transparent walls of ghostly blue ice. When I later showed the photos to the Locals, they also found it very impressive.

From the glacier down is a long downhill stretching more than ten kilometres, if you do not have a good lunch and road meal, fatigue on the body and mind will be as tortured as this long downhill.

PART VI: THE EDGE OF CIVILISATION

As we approached the village, we met the official who had come on his rounds, and were surprised to hear that we had tumbled over from Sapugangri.

‘Do you want food? Do you need red bull? You must be careful, there are a lot of bears here.’

‘Thanks, I’ll take a couple of bottles of Red Bull, I might be able to use them.’

I looked at the iron gates of the villagers’ houses on the roadside, which were welded with metal spikes, this was probably their way of preventing bears from banging on the gates.

From Naruo you can go straight out of the wild, the landscape up to this point is all snow-covered wilderness, if you want to explore more valleys and more types of landscapes, you need to go over the Yingzui Pass at more than 5,400 metres, which is the toughest pass of the whole trip there.

After mid-September, the pass is covered in snow, there is no trail and every step is fraught with danger.

If you are as lucky as we were to get over the pass, the rest of the trip is sure to be a pleasant surprise.

Before our encounter with the bear, the mood was subdued, eight days of walking through barren, uninhabited terrain, and since the encounter with the bear at the top of the text, the landscape has started to change, forests have appeared, rushing rivers have appeared, the trees have become thicker and stronger, and more colours have started to appear, no longer a world of blues, whites, and greys.

There are times when we yearn for snowy mountains. But after staying for a long time, I still feel that an environment full of life is more suitable for human survival. Suddenly I remembered a beautiful young Tibetan girl I met in the mountains of Aba, Sichuan province, who told me unreservedly while milking a yak.

‘I don’t like it here at all, I want live in Chengdu.’

For the women living in the Nyingchi Tanggula mountain area, there would not be those thoughts of the Aba girl, who had been isolated for a long time and could not even communicate with us.

When we wanted to stay overnight, we could only ask the female members of the team to come up and say hello first. Because in this season, most of the people staying in the mountains are women. If I had asked alone, I would have likely been rejected and even scared them away.

After establishing initial trust, it was time to communicate with postures and gestures that people all over the world can understand, such as folding your hands and putting them by your ears to mean that you want to find a place where you can sleep.

Our last night in these mountains was spent in a house whose walls were plastered with yak dung. The houses in this village are heavily clad in chipped wood, presumably to protect against bears. It was strange to sleep against yak shit, but it didn’t leak and it was safe.