Adventure Report: The Secret Realm of Gyirong

Team member: Liu Yu, Liang Xueyan, Mingyue, Longkui, Chengjin, Shanren, 2+2, Xiaoyao, Suqiao, Junfeng, Shouhu, Lijiangrong

Time: October 2025

Length: 60km 7 days

Location: Himalayas

Difficulty: 7.5/10

“It’s all snow-capped mountains, just like the EBC,” Daxiang said, holding his beer glass. “The only problem is the pass—it’s hard to cross. Step down, and the snow comes up to thighs.”

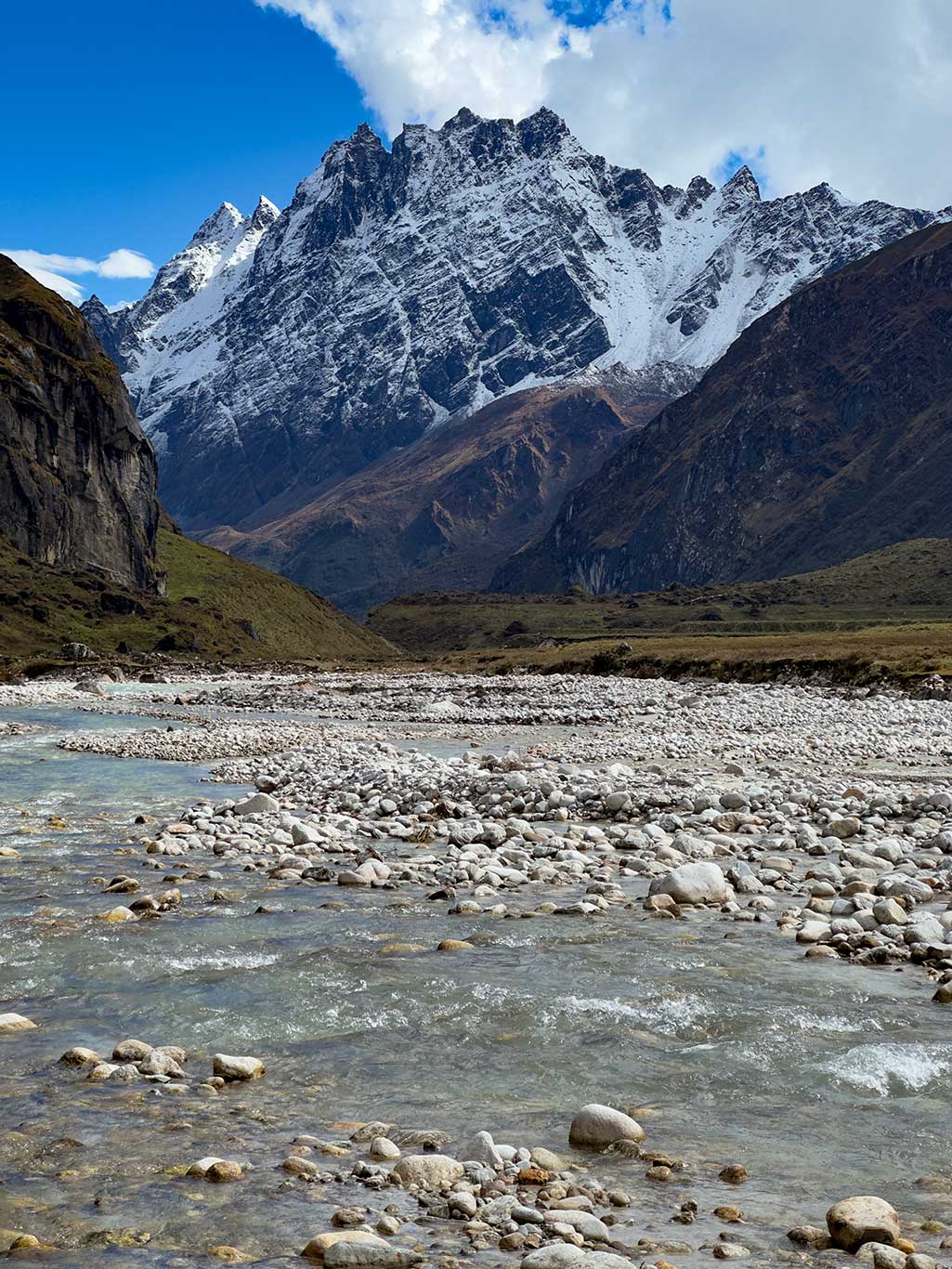

His words immediately drew me in. You can imagine it: a valley flanked by 6,000–7,000-meter snow-capped mountains, towering into the clouds, breathtaking scenery everywhere. And then a pass, like a snow-capped peak, waiting to be challenged. Any adventurer would be captivated.

“What’s the route called?” I asked.

“Actually, Dong Fei just drew a circle on the map,” Daxiang replied.

In 2024, my friend Daxiang (trail name) and Yan Dongfei’s team explored an unnamed valley on the southern slopes of the Himalayas. Since it is near Gyirong(Jilong) Valley, they named it the Secret Realm of Gyirong.

From satellite maps, most of this valley is at relatively low elevation with rich vegetation. In autumn, the colorful foliage would add to the already magnificent snow-capped mountains. The route is on the southern slopes of the Himalayas, directly affected by warm, moist air from the northward Indian Ocean currents, resulting in abundant precipitation. This means snow above the snowline will be thick, and we must be prepared with snowshoes to pass efficiently.

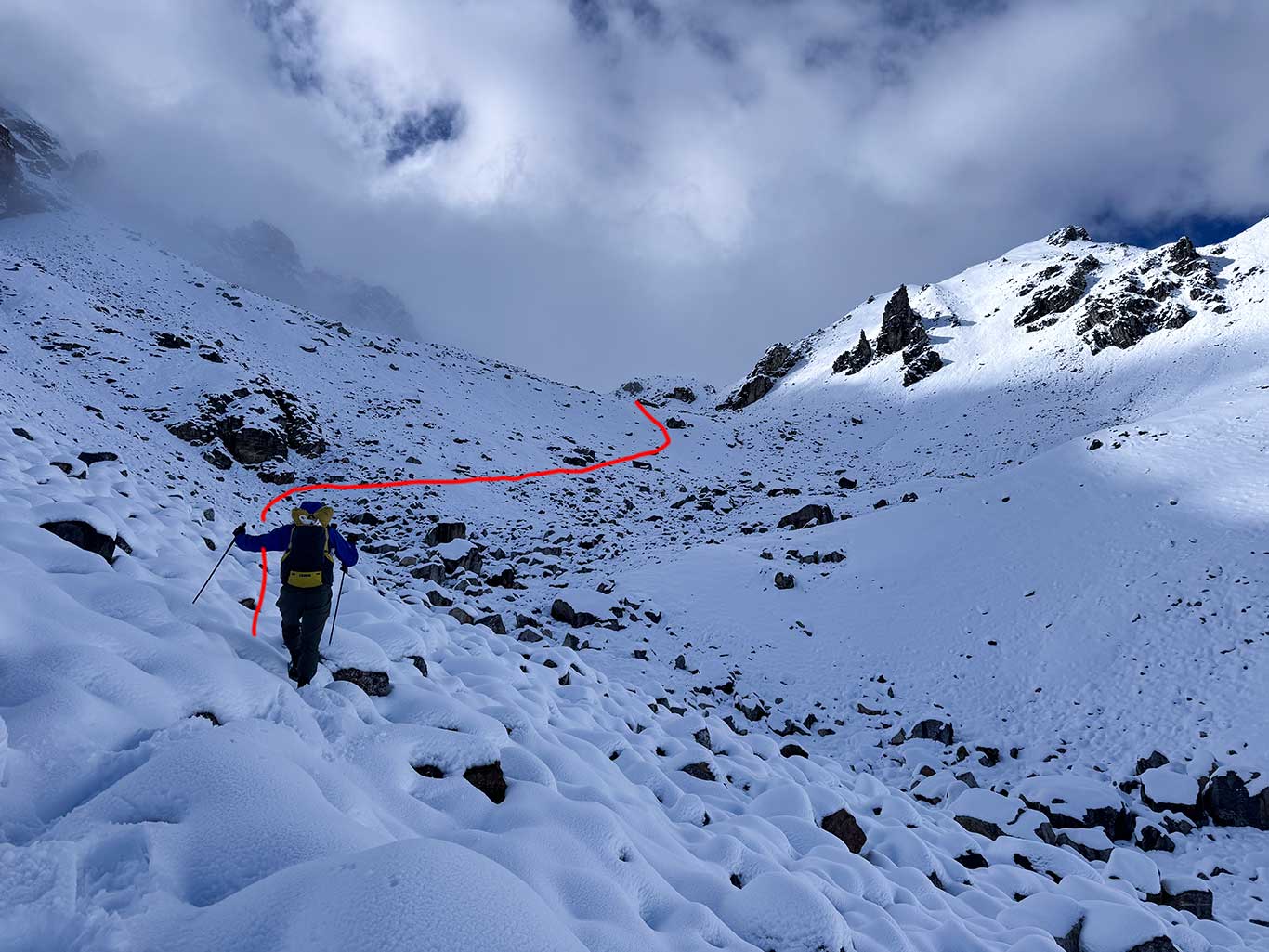

The route starts at Zhuo Village on the west side of the Donglin Zangbu Valley. Heading north, the valley splits into a group of mountains at a summer pasture called Langpu. The core challenge of our expedition was figuring out how to cross this mountain cluster and link the two valleys into a loop. The mountains separating the valleys exceed 5,000 meters, appearing nearly impassable on the map, but Yan Dongfei’s team found a pass at 5,100 m. In fact, this pass had been traversed before. Although there was no trail and everything was covered in snow and loose rock, a mani stone pile was found atop the glacier, likely left by Tibetan herders. The time of their passage could not be confirmed, as there were no signs of recent human presence, no camps, no debris.

This route shares a trait with last year’s Tianshan route: it is more akin to snow-mountain climbing than trekking. I therefore recommend that hikers carry the suggested mountaineering equipment. Snowshoes are essential; crampons are mostly unnecessary due to the deep snow. The route’s difficulty is concentrated over two days crossing the 5,100-meter pass; the remaining days are relatively easy.

Adventure Report:

How to get there:

Shigatse(Rikaze) is the closest transport hub to Gyirong Valley. You could fly closer to Dingri Airport, but flights are limited. I generally recommend flying to Peace Airport. From Shigatse, the only option is by car: private hire costs ¥2,700, while public transport is much cheaper but requires advance booking.

From Gyirong(Jilong) town to the trailhead, it’s another two hours over poor roads, requiring a local 4×4. Cost: ~¥700.

Day 1: 17 km, ascent 828 m, descent 304 m

Zhuo Village 3,400 m – Langpu 3,400 m – Baiku 3,830 m – Mantang 4,015 m

We didn’t stay in Gyirong town, instead staying at Nai Village like my friends, a famous viewing platform. Unfortunately, we had no luck seeing the snow-capped mountains. I don’t recommend staying in Nai Village: it’s not on the main route, and the next day requires backtracking to Gyirong town, losing an hour of sleep. Accommodations are also inferior to the town.

Returning from Nai Village involves a winding mountain road through the town, then east to the trailhead at Zhuo Village. Along the way, you pass Zha Village and a mountain pass over 4,000 m.

Zhuo Village, on the west side of Donglin Zangbu Valley, is small, clean, and tidy. From here, you can see a dramatic waterfall on the east valley wall and the snow-capped Langdang Lirong (7,227 m) and its satellite peaks to the south—a truly spectacular view. This village has enormous potential for tourism development.

The first half-day of hiking is easy: broad farm roads suitable for motorcycles, passing two beautiful summer pastures, Lemtang and Langpu. At these lower elevations, moisture is abundant, and tall pine trees cover the valley. Flat, tidy grass lies beneath. In the forest, one can find edible red and purple boletus mushrooms, often collected by locals, though proper cooking is required to avoid poisoning.

Between Lemtang and Langpu is a wooden bridge; I recommend crossing 1–2 people at a time to avoid collapse.

Langpu is at a river confluence: left leads to Sangbudo pasture, right to Mantang. Like Daxiang’s group, we went right, though in hindsight, the left route would have been more logical.

Beyond Langpu, vegetation changes noticeably: tall forests thin and vanish, waterfalls crash against dark boulders, and white water roars through the valley. Trails narrow, shrubs appear and gradually replace the forest. By Baiku, almost no trees remain; low shrubs indicate an altitude near 4,000 m.

For those aiming to see the 7,300-meter Gangpengqing Mountain, this is the ideal campsite. The next day, you can travel light to the east valley. We continued north, as fog and rain began to pour in. We had to reach Mantang before the rain worsened, where shepherd huts provided dry warmth.

Day 2: Rest or light trip to northern valley (easy reconnaissance)

After arriving at Mantang, we tackled the dilapidated cow shed. We thoroughly cleaned the floor and repaired the roof, yet the nighttime rain still reminded us of Mother Nature’s power. The rain continued the next day. A few team members went north to view the snow-capped mountains, but saw nothing, the clouds and fog were thick. We were forced to stay another day in the cow shed.

Day 3: 5.47 km, ascent 741 m, descent 53 m

Mantang 4,015 m – Advanced Camp 4,650 m

The morning started with decent weather, though cirrus and altocumulus clouds were visible. High-altitude winds from the south indicated changing conditions. We aimed to reach the advanced camp during this brief window.

In 2024, Yan Dongfei’s team had camped among boulders at 4,570 m. This time, with 11 team members, that site was too small. We chose a flat area near a cirque lake on the left side of the valley, at 4,650 m. The topography was flat according to the map.

The trail disappeared shortly after the start. Above this point, there was no vegetation, only a sea of loose rock and boulders. Even yaks avoided it. The cirque lake platform lay approximately 700 m west of the summit route, requiring cross-country travel that consumed considerable energy. Sudden weather changes and low visibility compounded the difficulty.

When we reached the platform, the cirque lake wasn’t visible, it lay behind a ~20-meter rock escarpment. We searched along the escarpment for water and fortunately found a spring beneath a massive black rock wall, saving the effort of hauling water over the escarpment.

The camp itself was nearly perfect: flat, moss- and grass-covered, geologically stable, and surrounded by mountains, a fine viewing platform. Shortly after setting up, snow began to fall, growing heavier.

Day 4: Blizzard, waiting at camp

The blizzard and thunder tormented our mind. Some teammates considered retreat, but I reassured them that the camp was safe: away from rockfall and avalanche zones, sheltered from the wind, and enough food. We only needed to wait for the north wind; that would signal the time to depart.

Snow accumulation required clearing the tents every 20 minutes, or risk collapse. Snow piling around the tents blocked ventilation. Everyone used trekking poles to prop open tent vestibules. At high altitude, ventilation is far more important than insulation; proper oxygen intake is critical. AMS (acute mountain sickness) is a serious risk here.

That afternoon, I called my wife via satellite phone to check the weather. The forecast was encouraging: high pressure would arrive, north wind would come, and the snow would stop.

At 3 a.m., the snow eased. Finally, the last tent clearing before sleeping. I went outside and used a frying pan to clear snow around each tent, ensuring the bases had ventilation gaps. I walked the camp perimeter to check that everyone’s tents had sufficient ventilation, then finally returned to sleep.

Day 5: 6 km, ascent 610 m, descent 493 m

4,650 m Camp – 5,100 m Pass – 4,779 m Camp

Morning was overcast; we waited until ~10 a.m. for the sky to clear. High pressure arrived, north winds blew away clouds, and the sun emerged, blindingly bright. The surrounding scenery changed dramatically: the colorful vegetation disappeared, replaced entirely by white and black. Strong UV felt like a furnace on the body.

I decided to move immediately. If temperatures continued to drop, snow would freeze into ice, making the stone slop dangers.

Descending to the valley bottom consumed enormous energy. I would not recommend this campsite to future trekkers; reverse traversal may be better.

The valley floor to the north was covered by snow over the boulder field, visually flat but dangerous without snowshoes, as hidden gaps in rocks could cause injury.

Above 4,600 m, no trail existed, only a boulder sea, extending to the 5,100 m glacier. Using snowshoes allowed us to float on the snow. In summer conditions without snow, our tracks would not be a useful reference.

After reaching the 5,100 m pass, a very steep descent led to a glacier. In other seasons, crampons and ice axes would likely be necessary due to crevasses. We descended approximately two hours to a flat snow-covered camp as darkness fell. Temperature was estimated near −10°C, evidenced by tent stakes freezing solid quickly in the snow.

Day 6: 13.37 km, ascent 283 m, descent 942 m

4,779 m Camp – River Junction Camp 3,967 m – Crossing – Xiare 3,945 m

Morning temperatures were extremely low, likely −15°C. High pressure persisted, sky was clear. Everyone’s shoes were frozen solid and had to be thawed over a stove before wearing.

I used hot water in insulated bags and Kandy Befree water bag inside sealed insulation, both to retain heat and protect my water purifier from freezing. With a 300 g sleeping bag and full insulation system (down blanket, pants, foot covers, Climashield jacket), plus hot water bag, I stayed warm even in this cold. The camp’s location on a saddle prevented cold air pooling.

Descending to the valley floor was quick. We followed the left side of the river as Daxiang advised, proving wise. At 4,100 m, trails reappeared, speed increased, and vegetation grew richer.

Near the river junction, we found an excellent campsite, flat, clean, and close to water. Another advantage: morning river levels were low, easing the river crossing ahead.

We mistakenly judged the next section and had to backtrack 2 km after encountering a waterfall and cliff. Across the river, a deserted pasture house was filthy with spoiled milk and cow dung; we camped outside instead of inside.