The No Man’s Wilderness : White Lake Loop in Altai Mountains.

Team member: Liu Yu, Zi Long, Jun Dao, Kuai Le, Cha Ye

Time: October 2016

Length: 250km 14 days

Location: Altai Mountains

Difficulty: 8.5/10

Among China’s most challenging trekking routes, Langta, Xiate, HuanBogeda, and Aotai are well-known for their extreme difficulty. Some organizations rate them as nearly top-tier in terms of challenge. Beyond these, there are other expedition-level routes like Keriya, the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, and various crossings in the Changtang region. These routes are harder to classify due to unpredictable weather, undeveloped trails, and uncontrollable risks. After this expedition, it’s clear that the White Lake Loop in the Altai Mountains belongs to the latter category.

This journey lasted 14 days, 250 kilometers, with 4 of those days packrafting. This trip is the first documented expedition that someone has completed this full White lake Loop using packraft. We are the second team to complete the White Lake loop.

1. First Encounter with White Lake

I first stumbled upon this route while casually browsing Google Earth, searching for unknown trails. White Lake is not far from Kanas Lake, separated by a 50-kilometer valley that looked intriguing. Later, I discovered that a man named “Liuxing2008” in BBS had already traversed it, followed by the well-known incident of another hiker named “GongBing” died in this area, He was the first person to attempt to explore this circuit with a packraft, but sadly he didn’t make it out alive.. In 2015, a team led by “Jumer” successfully completed the crossing with his packraft, But at the end of the day, he chose to ask for help from the ranger station at the confluence of the White Lake and the Kanas River. Riding out on horseback round the corner. In a sense, not completing the route.

What sets White Lake apart is its diversity: stunning landscapes, varied terrain, rich plant and animals, and the integration of multiple outdoor activities. Looking back, a complete White Lake expedition requires hiking, basic glacier travel skills (we didn’t plan to climb glaciers, so we didn’t bring mountaineering tools—a regret), and some packrafting skills. Thus, our White Lake journey wasn’t a typical trekking expedition but rather a blend of hiking and packrafting, a new sport originating from Alaska that involves carrying inflatable rafts for river crossings.

The White Lake Loop consists of the following sections (not in chronological order):

Type | Route (Estimated Distance) | Difficulty |

Established Hiking Trail | Tübek – Kanas (25 km); Jiadengyu – Hemu (30 km) | Easy |

Unmarked Paths | Hemu – 2600 Ice Lake Pass – East White Lake (100-120 km) | Middle to Hard |

Off Trail | Southwest White Lake – Middle Kanas River Valley (30 km) – Lake Head (25 km) | Hellish |

River | White Lake; Lower Kanas River (Class 1-2) – Kanas Lake (50 km) | Dangerous |

Note: If you choose not to raft the middle section of the Kanas River, you can attempt to hike out off trail, making it extremely challenging—this feedback comes from our three teammates who didn’t raft.

From the table above, it’s clear that White Lake is not a hike trail. “Liuxing2008”, in his travelogue, recalled the route as perilous and advised against attempting it. Now, having completed it, I fully understand his warning. After emerging from the wilderness, locals were shocked to hear about our journey. Even to them, that area is a forbidden zone, home to wolves and brown bears, with many hunters and villagers having gone missing there in the past.

2. Preparations

Since this trip involved packrafting, our base weight increased significantly, making lightweight gear essential. Due to personal reasons, my preparation was rushed—I only had one day to pack. My main food supply was Shanzhichu, something like Mountain House, a freeze-dried meal brand, and other snacks were hastily bought from Walmart. My basic gear was similar to what I used on the Aotai trek earlier in the year. The main differences were leaving behind my rain jacket and bivy sack, adding extra warm clothing like down pants and light fleece. I boldly opted for Brooks trail-running shoes, bringing only one pair of Smartwool socks and alternating them with Dexshell waterproof socks. For fuel, I stuck with alcohol, increasing the quantity to 500 ml. Thanks to abundant natural fuel sources, I had about 80 ml left by the end.

For packrafting, I used Jumper’s new mini backpack frame paired with Sea to Summit dry bags, ensuring 100% waterproofing. My raft was the Klymit LWD, weighing only 990 grams, and my paddle was a OYMG carbon fiber one, totaling 440 grams. However, during the river section, I switched to a teammate’s abandoned PP paddle. For rafting gear, I only brought a Stohlquist dry top and a buoyancy vest, which proved insufficient—my lower body froze. Lesson learned: always bring your best drysuit and PFD, no matter the weight.

In any expedition, you must have contingency plans for potential risks—it’s like not leaving a blank answer on an exam. Bears were a major risk on this trip. We bought bear spray, carried by my team mate“Zilong”, while I brought a small 50 ml canister, which I lost midway.

My total pack weight, including 11 days of food, was around 16 kg. There were two resupply points: Hemu and Tübek, so I didn’t need to carry 13 days’ worth. If you’re a skilled angler, you could also consider fishing for food.

Our team consisted of five people initially, but some dropped out due to personal reasons. In hindsight, those who dropped out were lucky.

3. 4,000 Kilometers to White Lake

We flew from Jinan to Urumqi, picked up the bear spray (which couldn’t pass any security checks in Xinjiang), and hired a private car to Kanas. We arrived at Jiadengyu in the middle of the night and quickly found a yurt for about 50 yuan per person.

The 30 km hike from Jiadengyu to Hemu was good trail, so we chose to walk it in one day. My feet were killing me, and the scenery was just average.

Hemu was bustling with tourists, and accommodation was expensive. To find a cheaper place, we hike 2 km into Hemu and found a Kazakh family who charged 50 yuan per person, complete with a warm stove.

The next day, we crossed a newly built wooden bridge in Hemu and headed north. The scenery was much better than in Hemu, with yellowing leaves and a serene, untouched atmosphere.

We passed several Tuvan cabins, mostly inhabited by elderly people, as the younger generation had moved away from the mountains. The Tuva people, who are of Mongolian descent, depend on hunting for their livelihood and use homemade horsehide skis to go out into the forest in the winter in search of food.

Compared to Hemu, the people here were much more genuine. We encountered a family building a small cabin. Though they didn’t speak Mandarin, they warmly invited us into their home, treating us to naan bread, small potatoes, milk tea, and wild blueberry jam. Seeing their humble lifestyle, we offered money, but the elderly woman didn’t even look at the amount, simply placing it beside the food. As we left, she noticed Zilong loved the potatoes and gestured for him to take some, but we declined, not wanting to take from their limited resources.

As we left the sparse Tuvan village, the trail became less visible, filled with fallen trees, bushes, and swamps. It felt like someone had deliberately blocked the path, but it was just nature. Every few kilometers, we’d find a campsite, likely used by locals for hunting or fishing.

On the third day, I felt unwell, likely due to food poisoning from drinking unfiltered, only boiled stream water the night before. The water probably came from a nearby swamp, containing excessive organic matter. I was weak and had to stop to rest after only 3 km, which felt like 30 km. That night, I drank Zilong’s rice soup, vitamin C water, and Kuaile’s honey, along with antibiotics and fever reducers. After a night’s rest, I could walk again, but it was still agonizing. I discovered that whenever my stomach hurt, shitting would buy me 1-2 hours of relief. Over four days, I finished all the antibiotics, and my stomach slowly recovered. From then on, I only drank filtered and boiled water, and had no further issues.

The campsites along this section were well-maintained, with flat ground, fire pits, and chopped firewood, likely used by locals. However, we had to be careful with fire, ensuring it was completely extinguished and cool to the touch. In some areas, the thick layer of pine needles and decomposing soil was highly flammable, and a small mistake could lead to a massive fire—and a lifetime in prison.

After entering the Sumu River Valley, we used our packrafts to cross the river from the west bank to the east bank at approximately 48°45.8 N, 87°33.5 E. We crossed to bypass a 500-meter-high slope about 6 km ahead, which would allow us to avoid a high-drop section of the Sumu River. Before the slope, we passed a burned slope where the trees had been killed by a wildfire.

After crossing the slope, the turbulent Sumu River became calm, perfect for fishing—though we didn’t have the right tool. We used the packrafts to cross again, then hiked for two hours to a clearing in the forest to camp. If you have time, I recommend hiking another two hours to an ancient tree, which makes for a great campsite and even offers pine nuts.

Up to the 2600 Ice Lake Pass, the trail was discernible, and we could replenish water. We even picked wild blueberries along the way. The Ice Lake was small but beautiful, its blue waters contrasting with the sky. As we descended past the lake, the trees disappeared, leaving only a desolate plateau. The mountains weren’t steep, but their grandeur was amplified by the shadows cast by the clouds. For a moment, we were all mesmerized. A small east-west trail led from Mongolia to the glaciers beneath the western snow-capped mountains—who knows what lies beyond.

On the descent, we veered off course, trudging through swamps, boulder fields, and dense bushes taller than a person. It was utterly exhausting. After crossing the river, it was already dark, and finding the trail was difficult. We struggled for four hours before finding an abandoned shelter that had existed for at least a decade. We squeezed five people inside for the night, staying relatively warm.

The trail to White Lake was tough, likely due to its lack of visitors. Along the way, we found a patch of wild boar hair and a small piece of skin—likely the remains of a large predator’s meal.

About 7 km west of the abandoned shelter, we reached the eastern inlet of White Lake by noon. There was another hunter’s shelter, newer and more comfortable, with a stone stove that seemed well-used. We camped here, Zilong and I decided to sleep inside the shelter, waiting to cross White Lake the next day. In the afternoon, we washed our clothes and warmed ourselves by the fire, enjoying a sense of normalcy.

We tried fishing in White Lake but caught nothing. The water was a murky white, devoid of life, almost as if it were toxic. However, locals claim the lake is teeming with fish—so much so that a horse handler wanted to buy our raft for fishing. That night was the most comfortable of the entire trip, with the shelter’s temperature reaching 20°C while it snowed lightly outside.

4. Into the Dark Forest

For many previous teams, White Lake was a major obstacle, a stumbling block in the middle of the loop. The steep slopes on either side made it impassable. With packrafts, however, crossing White Lake became a leisurely activity. Zilong and I used the Klymit LWD, while Jun Dao, Kuaile, and Chaye used air force life rafts. Both types of boats worked for crossing White Lake, though the air force rafts were deeper and prone to taking on water.

Paddling on calm water was peaceful but eventually boring due to the slow speed. Fortunately, the weather improved, and the distant mountains gradually came into view. After about three hours, we crossed White Lake and landed on the southwest shore.

Shortly after landing, we stumbled upon fresh bear tracks—apparently, bears like to travel in groups. It was genuinely frightening.

Next, we followed the east bank of the Kanas River into the primeval forest. There was no trail after landing; we had to climb over a hill for a few kilometers, easily losing our way. We then followed slippery riverbanks, occasionally entering boulder fields—utterly frustrating. Thankfully, our packs were light; I can’t imagine doing this with a heavy load. As night fell, we hastily found a “flat” spot to camp. The next morning, a fire patrol helicopter flew overhead, later learning it was searching for missing hikers.

We put a lot of energy into putting out the campfire, the leaves of the pine trees piled up several metres high and we ignited the rotting material underneath, so much so that we spent an hour constantly fetching water from the river to get the campfire to stop smouldering, we used hundreds of kilos of water.

I could use the worst words to describe the east bank of Kanas River—there were too many issues to list. This experience solidified my decision to raft, while Jun Dao, Kuaile, and Chaye chose hike out. Chaye later recalled that hike as hellish, with not only difficult terrain but also bear scat and tracks everywhere, a mental and physical ordeal.

A Peculiar Tree: ‘Welcome to Hell.’

About halfway through the Kanas River Valley (around 49°0.2 N, 87°20.58 E), the river’s flow slowed, and the channel widened. At an elevation of about 1,400 meters, with a 100-meter drop to Kanas Lake, Zilong and I decided to raft out after lunch, leaving the others with bear spray and two packs of Shanzhichu meals.

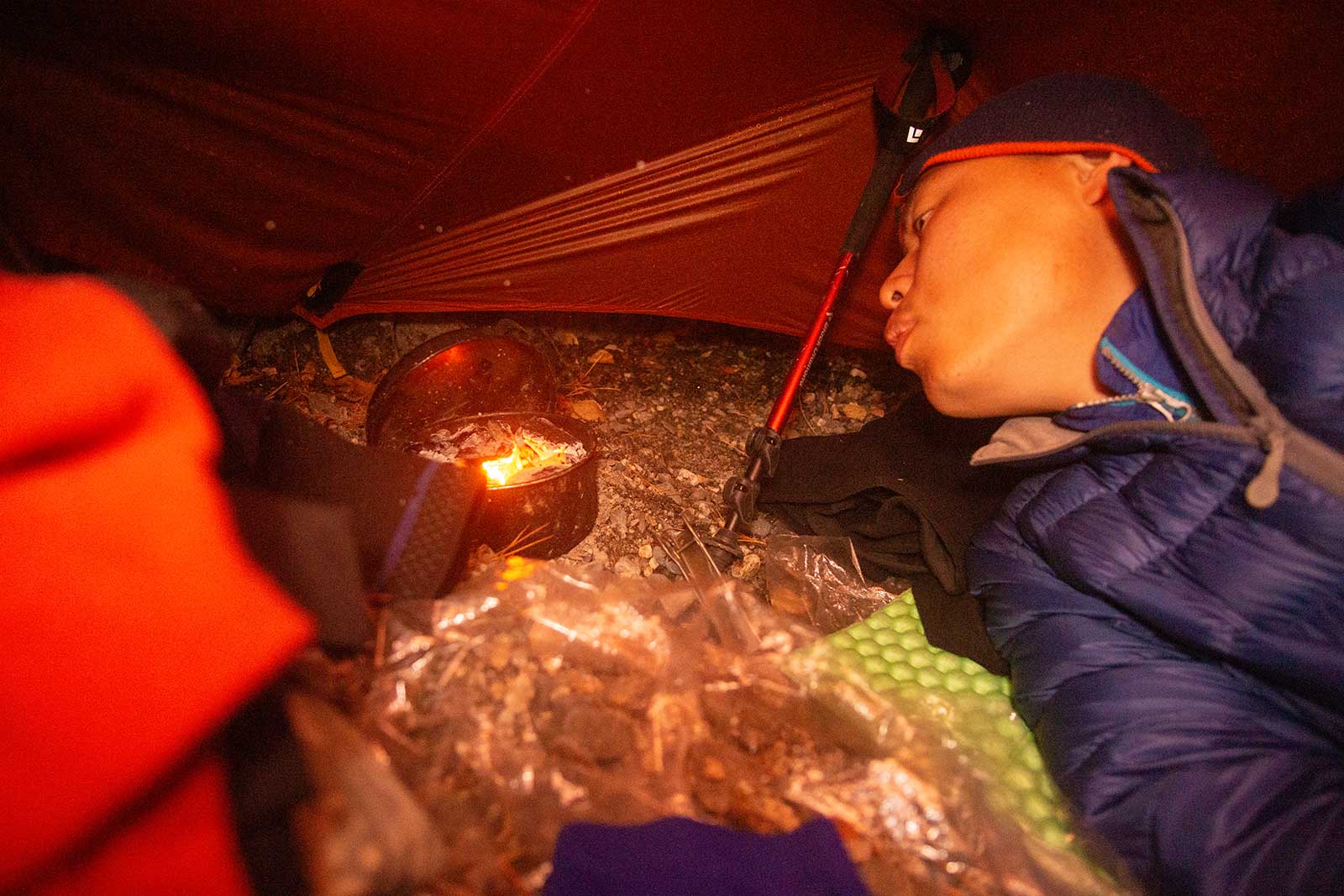

The first two hours of rafting were recorded on video, but things didn’t go smoothly. Shortly after starting, a cold rain began, and two hours later, we hit a rapid. While scouting the rapid, I accidentally punctured my boat on a sharp rock, forcing us to stop for repairs. Zilong and I showed signs of hypothermia, so we quickly set up camp, ate the last of our chocolate, lit a fire, changed into dry pants, and recovered. The boat was patched, but the rain returned, so we stayed in the tent with a small fire, eating pine nuts and staying warm.

The next morning, Jun Dao and the others spotted our camp from the opposite bank. After confirming everyone was safe, Zilong tossed them two more packs of food, as they were running low on food due to the strenuous hike. We hiked around the rapid and continued rafting. Unfortunately, our GoPro had died by then, and with the lack of sunlight, all our electronics were running low. This section of the river was the most scenic, the highlight of the trip, but sadly, we have no footage.

Afterword: On this section of the trail, a huge disagreement arose between us about whether to walk or raft. The reason for this was that each person had a different perception of the difficulty and risk of the route.

Disagreements, if handled well, will be a huge encouragement to the morale of the team, otherwise they will destroy the team.

5. Breaking Out of the Wilderness

The final day of rafting was blessed with good weather—sunny and not too cold, even a bit warm. As we approached Kanas Lake, the river slowed and split into multiple channels. We followed the largest flow but encountered two logjams blocking the way, forcing us to disembark and hike around. You had to plan your exit early; getting stuck on a logjam would’ve been awkward. The water level wasn’t high this season, but the rapids could still reach Class 2-3, so we had to stay alert.

It took about two hours to reach Kanas Lake. Exiting the river, we found ourselves on a small tributary, which was puzzling. Looking east, the main channel’s turbulent waters collided with the lake, creating massive waves.

After landing on Kanas Lake, we dried our gear and tried to find a trail but failed. We continued paddling until evening, then camped onshore. I slept soundly but was woken by Zilong in late night. He asked nervously if I’d heard something bumping the tent. I said no and went back to sleep. In the morning, he explained he’d had a nightmare about a bear attacking the tent and tried to scare it off by mimicking animal growls.

The next morning, we paddled further and found a clearing with construction materials, likely a temporary port used by locals for transporting goods. Walking inland, we discovered a garbage dump, indicating a nearby village. Sure enough, we soon found the village, an unexpected but welcome surprise.

The village, called Tubek, is a stop on the well-known “Kanas Grand Loop Trail” and remains relatively untouched by modernity. We stayed at a guesthouse run by a Kazakh woman married to a Tuvan man. Their photo was on the sign, and they seemed very loving. That night, we asked the hostess to prepare 5 pounds of lamb and shared a meal with Pan, a solo hiker we met in the village. They craved the local beer, but I avoided it due to a bad past experience and opted for alcohol instead. Pan had worked at The North Face and knew a lot about outdoor gear, so we hit it off. That night, we contacted Jun Dao and learned they’d just emerged from the wilderness, finally putting our minds at ease.

The next morning, we were woken early by another team’s leader insisting on an 8 AM departure (6 AM local time, before sunrise). It was freezing, and some team members grumbled. Around 10 AM, the three of us set off on a wide horse trail, enjoying the ease of the path. Without lunch, we headed straight to the Tielishagan Ranger Station for a meal. The young ranger made the best “Shou Zhua Fan” (Lamb and vegetables rice) I’ve ever had. An older ranger, who’d worked there for eight years, enthusiastically advised us on how to bypass the Kanas ticket checkpoint.

As we neared the checkpoint, Pan decided to visit the Fish Watching Pavilion, and we parted ways. We then called the Kanas hotel owner, who picked us up. He mentioned that this year’s National Day holiday visitors was unusually small, which was strange. Back at the hotel, the owner’s family was shocked to hear we’d been to White Lake and eagerly asked to see photos, expressing interest in getting a boat to fish there. Dinner at the hotel was leisurely—two hours for a plate of “Shou zhua fan” and a stir-fry. A group of girls on a leisure trip, starving, asked for a bite of our rice. When their food arrived—a whole roasted lamb—they repaid us with half a lamb leg, It’s a lucrative return on investment.

The next morning, the hotel owner helped us catch the free bus to Jiadengyu, where we transferred to another bus. As we left, Kanas was hit by heavy snow. The Kazakh driver, thrilled, kept saying how lucky we were to get out before the storm.

After a long journey back to Urumqi, Zilong and I wandered through the alleys behind Erdaoqiao, near the old flea market. We tried a variety of local Uyghur snacks—delicious, cheap, and hearty. Later, when chatting with a friend from Xinjiang, they were shocked: “You actually went there?!” I replied, “We’ve already braved bear territory. What’s there to be afraid of?”

Summary:

This is the most challenging expedition I have ever undertaken. The risks include dense wildlife activity, extremely long off-trail treks, limited reference information, and threats from poachers. Only a very few have completed the entire journey, while most teams had to abandon their trips midway.

Due to no trails, we ultimately had to resort to using an ultra-light inflatable boat to navigate the Kanas River, a highly perilous choice as such boats are only suitable for still waters.

In these mountains, September is the window period when the river flow is lower, bears are less likely to attack humans, and the snow is not too deep. However, during other seasons, it can be extremely dangerous.